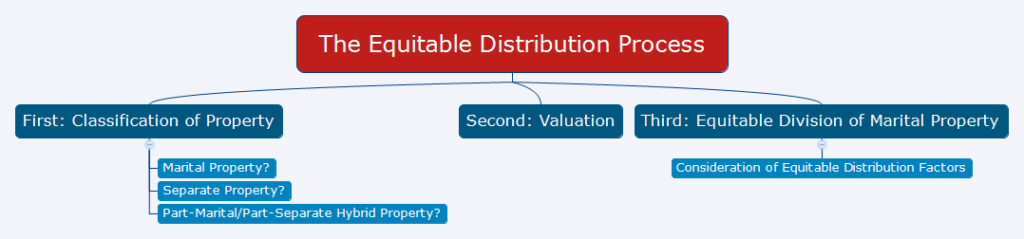

Navigating Equitable Distribution in Your Virginia Divorce: A Guide

Understanding how Virginia divides marital property in a divorce can feel overwhelming, especially with complex legal terminology. This guide aims to simplify the process by focusing on the key concept: equitable distribution. Virginia Code § 20-107.3.

Step 1: Classifying Your Property

“Property” include all imaginable types of property from jewelry and bank accounts to investments and retirement accounts. Before dividing property, the court must determine which assets have legal grounds for division. This involves classifying them into three categories:

- Marital Property: This includes all property acquired during the marriage by either spouse, jointly owned property, and income earned during the marriage.

- Property acquired after the separation of the parties is presumed to be separate property.

- Separate Property: This includes property acquired before the marriage, inherited or gifted assets, and property acquired with the proceeds from separate property sales.

- Hybrid Property: This is a combination of both marital and separate property. The concept of hybrid property is used to avoid the inequity of past practices that treated all co-mingled property as marital property regardless of any separate investment. It may arise when separate property increases in value due to efforts by one or both spouses during the marriage including either direct effort or the investment of marital income in the property.

- For instance, hybrid property is created when a spouse pays the down payment on a home, with money he or she owned prior to the marriage, but then the mortgage is paid with income earned during the marriage.

- To make things even more complicated, parties frequently argue whether inflation in value is due to market influences outside their control and thus either should or should not be deducted from any increase in value during the marriage. Personal investment accounts often exist in the middle of these types of dilemmas.

Contrary to popular belief, co-mingling of separate and marital property does not result in a presumption that the entire property is marital. In other words, jointly titling property does not give rise to the presumption that the separate property was gifted to the marriage. Despite joint titling, either party is permitted to trace separate property and ask for a hybrid classification by the court.

Step 2: Valuing Marital and Hybrid Property

Once classified, the court needs to determine the “intrinsic worth” (often the “fair market value”) of marital and the marital portion of hybrid property. This typically involves:

- Expert witness testimony: Appraisers are often used for valuable assets like real estate or businesses.

- Agreed-upon valuations: Lawyers may settle on a value without involving experts to reduce costs.

- Court-assigned valuation: If no agreement is reached, the court sets the value.

The value of property may be adjusted.

Liens on property, such as mortgages or car loans, must also be accounted for when valuing property. If a spouse has paid down a loan during the parties’ separation then the increase in equity resulting therefrom may be considered that spouse’s separate property and be deducted from the final value used by the court.

Costs of selling the property such as broker’s fees in the case of houses may also be taken into consideration under certain circumstances.

Proving the value of marital property:

A court cannot guess at the value of property. The parties may give their opinions as to the value of property but they are not always very convincing when it comes to valuable items. Expert witness testimony from appraisers is frequently relied upon to establish the value of significant assets such as real property (homes and land) and business interests (such as family businesses or professional partnerships). However, an owner’s opinion as to the value of property may also be considered.

To avoid the costs of expert witness appearance fees and trial preparation of experts, divorce lawyers frequently obtain appraisals and try to reach an agreement on valuation prior to trial. The use of agreed upon neutral appraisers, tax assessed values, Kelley Blue Book values and similar resources may significantly lower the costs of divorce litigation.

Different valuation methods may be used depending on the property being valued. Alternate valuations techniques, usually using expert testimony, are most common when dealing with complex assets such as business interests, professional partnerships, certain investment devices, etc.

When property is subject to changing value over time, such as investment accounts, a “valuation date” must be used to set the value.

The valuation date is usually the date of the final divorce hearing. However, retirement accounts are usually valued as of the date of separation. Equitable distribution evidence is almost always heard with all other evidence at the final divorce hearing. In rare instances, equitable distribution evidence is heard separately in what is referred to as a “bifurcated divorce”.

Either party may request that the court use a different valuation date but the court is not required to do so. A request for the court to use a different valuation date must be filed no less than 21 days prior to the equitable distribution hearing.

Step 3: Dividing Marital Property

Virginia law doesn’t require an equal split of marital property. The court considers various factors, including but not limited to:

- Each spouse’s contributions to the marriage and property acquisition.

- The marriage duration.

- The financial and physical condition of each spouse.

- Reasons for the divorce.

- Tax consequences of the division.

- Debts and liabilities of each spouse.

- Liquid or non-liquid nature of the property.

Key Points to Remember:

- Equitable distribution involves complex legal considerations. Consulting an experienced attorney is crucial.

- Courts have broad discretion in applying the factors, making legal representation even more important.

- Understanding the classification, valuation, and division processes can help you navigate your divorce more effectively.